An Informal Introduction to Ideas Related to KAM (Kolmogorov-Arnold-Moser) Theory

KAM theory has developed into a recognized branch of dynamical systems theory that is concerned with the study of the persistence of quasiperiodic trajectories in Hamiltonian system subjected to perturbation (generally, a Hamiltonian perturbation). The origins of this mathematical theory lie in attempts to understand the convergence of perturbation series solutions representing quasiperiodic solutions of the three-body problem in celestial mechanics [Mos01][BG97][Dum14]. Significant progress was made in this area in the second half of the twentieth century, and its name represents an acronym formed by the names of the three founders: Andrei Kolmogorov, Vladimir Arnold and Jürgen Moser. The main question that KAM addresses is the following:

What happens to the quasiperiodic trajectories of an integrable Hamiltonian system when the flow is modified with a perturbation that respects the symplectic structure of Hamilton’s equations? Will the perturbation destroy these quasiperiodic solutions, or is it possible that some of them will survive and only become slightly deformed?

The first answer to this question was provided by Kolmogorov in his famous plenary lecture [Kol57] at the International Congress of Mathematicians that took place in Amsterdam in 1954. Since the pioneering works of Poincaré on the three body problem, the intuition built into the scientific community was that typical systems in classical mechanics exhibit chaotic behaviour in some regions of their phase space. However, Kolmogorov’s remarkable announcement produced a complete shock that turned this view upside down. In his talk he claimed that for near-integrable Hamiltonian systems, that is, integrable systems subjected to a perturbation, almost all quasiperiodic motion persists. As we will explain in more detail shortly, quasiperiodic trajectories trace out tori in phase space. Indeed, they are often viewed synonomously with invariant tori. Moreover, it turns out that the quasiperiodic trajectories that lie on non-resonant tori are more robust to survive the perturbation than those associated to resonant tori. In fact, resonant tori are the first tori to disappear when the system is perturbed. Interestingly, among the non-resonant tori, KAM theory establishes a criterion to measure the “degree of non-resonance” that is related to their robustness with respect to the perturbation.

Despite the deep consequences and implications that the results presented by Kolmogorov would bring to the field of classical mechanics, he had only provided partial arguments for them and not complete mathematical proofs. Hence, the foundations of this new theory needed a rigorous scaffolding that arrived several years later, in the period 1962-1963, with the independent works of Arnold [Arn62][Arn63a][Arn63b] and Moser [Mos62].

The goal of this section is to provide the reader with a basic and brief overview of the mathematical ideas and concepts behind KAM theory, and how its development has contributed greatly to the recognition of this theory as an important achievement of the modern theory of dynamical systems. For the sake of clarity, we will avoid many abstract and technical details of the theory. Instead, we will focus on explaining the mathematics behind the terms we have highlighted in boldface in the text above, so that this can help us better understand the mathematical content of the questions introduced above in italics, and the answers to them provided by KAM theory. Most of the material discussed in this section is based on, and has been adapted from, the detailed and nice descriptions of KAM theory presented in the books [DH96][Dum14][Wig03]

For completeness, we begin our explanation of KAM theory by considering a Hamiltonian system with \(N\) degrees-of-freedom (DoF) defined by a scalar function \(H(\mathbf{q},\mathbf{p})\) known as the Hamiltonian, (see (1) ). This function depends on \(\mathbf{q} \in \mathbb{R}^N\), the configuration space coordinates that represent the DoF of the system, and \(\mathbf{p} \in \mathbb{R}^N\), which corresponds to their canonically conjugate momenta. In this setup, the phase space where dynamics occurs is \(2N\)-dimensional, and if we label a point in phase space as \(\mathbf{z} = (\mathbf{q},\mathbf{p}) \in \mathbb{R}^{2N}\), the evolution of the system’s trajectories is governed by Hamilton’s equations of motion:

(42)\[\begin{split}\begin{equation}

\dot{\mathbf{z}} = \mathcal{J} \, \nabla_{\mathbf{z}} H \quad \Leftrightarrow \quad

\begin{cases}

\dot{q}_i = \dfrac{\partial H}{\partial p_i}, \\[.4cm]

\dot{p}_i = -\dfrac{\partial H}{\partial q_i},

\end{cases}

\quad i \in \lbrace 1, \ldots, N\rbrace

\end{equation}\end{split}\]

where \(\mathcal{J}\) is the symplectic matrix (see (12) ) and \(\nabla_{\mathbf{z}}\) is the gradient operator acting on the Hamiltonian.

The value of the Hamiltonian corresponds to the total energy of the system, it is conserved along trajectories and therefore it is a constant of motion or a first integral of the system. Dynamics for a fixed energy is constrained to a \(2N-1\)-dimensional constant energy hypersurface embedded in the \(2N\)-dimensional phase space.

As stated in the introduction, KAM theory is concerned with perturbed integrable systems. In simple terms, a system is said to be integrable if one can find explicit formulas for its solutions, or at least, expressions for them that involve indicated integrals and elementary functions. As opposed to non-integrable systems, integrable systems admit closed form expressions for their trajectories, given initial conditions. This type of integrability is referred to as ‘’integration by quadratures’’ and was first developed by Liouville [Lio55].

Observe that a solution of a dynamical system is a trajectory, that is, a one-dimensional curve wandering around in the \(2N\) high dimensional phase space. Therefore, in order to determine this trajectory one would need to be able to obtain \(2N-1\) functionally independent constants of the motion (CoM), \(F_{i}(\mathbf{q},\mathbf{p}) = C_i\) where \(i \in \lbrace 1,\ldots,2N-1\rbrace\), so that the result of their intersection is the sought trajectory. This means that each CoM decreases the dimensionality of the accessible phase space for the system by one. Notice also that this approach of finding constants of the motion in order to determine the solutions of the system comes from the natural approach of integrating the \(2N\) ordinary differential equations that define Hamilton’s equations, an operation which would yield, if it can be carried out, \(2N\) integration constants that are later obtained in the classical way from initial conditions.

However, due to the special symplectic structure of Hamiltonian systems, in order to establish the integrability of a system we only need to find \(N\) CoM. This criterion is known as the Liouville-Mineur-Arnold Integrability Theorem [Lio55][Min35][Min37][Arnold13], and plays a key role in the development of KAM theory. This result states the following:

Liouville-Mineur-Arnold Integrability Theorem (LMAIT):

An \(N\) DoF Hamiltonian system is integrable if and only if there exist \(N\) constants of the motion \(F_1,\ldots,F_N\) which are smooth analytic functions of the phase space variables, such that:

they are functionally independent, which means that the vectors \(\nabla F_1 , \ldots, \nabla F_N\) are linearly independent for almost all phase space points,

they are in involution with each other, that is, \(\lbrace F_i,F_j \rbrace = 0\) for each \(i \neq j\).

Notice that the involution condition is equivalent to \(\nabla F_i\) and \(\nabla F_j\) being orthogonal in the symplectic sense

\[\lbrace F_i,F_j \rbrace = \left(\nabla F_i\right)^{T} \mathcal{J} \, \nabla F_j = 0.\]

This means geometrically that in the symplectic structure of Hamiltonian systems, the level hypersurfaces of the CoM in involution are orthogonal. The LMAIT criterion also ensures that if the intersection resulting from these CoM is a connected and compact manifold, it has the shape of an \(N\)-torus, denoted by \(\mathbb{T}^{N}\). Such an object is the result of taking the cartesian product of \(N\) copies of a circle, that is:

\[\begin{equation*}

\mathbb{T}^{N} = \underbrace{S^1 \times \ldots \times S^1}_{\scriptsize{\mbox{$N$ times}}} = \left(\mathbb{R} / 2\pi \mathbb{Z}\right)^{N}

\end{equation*}\]

The LMAIT result goes further by ensuring that for the phase space regions where one can find these tori, there exists a canonical transformation to action-angle coordinates \((\mathbf{I},\boldsymbol{\theta})\) such that the Hamiltonian in these new variables only depends on the actions:

\begin{equation*}

K(\mathbf{I}) = K(I_1,\ldots,I_N)

\end{equation*}

and Hamilton’s equations are given by:

(43)\[\begin{split}\begin{equation}

\begin{cases}

\dot{\theta}_i = \dfrac{\partial K}{\partial I_i} = \omega_i(\mathbf{I}) \\[.3cm]

\dot{I}_i = -\dfrac{\partial K}{\partial \theta_i} = 0

\end{cases}

\; , \quad i \in \lbrace 1, \ldots,N \rbrace

\end{equation}\end{split}\]

The action variables are \(N\) independent constants of motion and they only depend on initial conditions:

(44)\[\begin{equation}

I_i(t) = I_i^{0} = \text{constant} \quad \Leftrightarrow \quad \mathbf{I}(t) = \mathbf{I}_0 = \text{constant}.

\label{eq:actions}

\end{equation}\]

The actions determine the energy of the system,

\($

K_0 = K(\mathbf{I}_0) = K\left(I_1^0,\ldots,I_N^0\right),

$\)

and the differential equations for the angle variables yield:

\[{\theta_i(t) = \omega_i(\mathbf{I}_0) \, t + \theta_i^0 \mod 2\pi \;\; , \quad i \in \lbrace 1, \ldots,N \rbrace}\]

where \(\omega_i(\mathbf{I}_0)\) are the angular frequencies. We can write the angular solution in vector form:

(45)\[\begin{equation}

\boldsymbol{\theta}(t) = \boldsymbol{\omega}\left(\mathbf{I}_0\right) t + \boldsymbol{\theta}_0 \mod 2\pi

\label{eq:angles}

\end{equation}\]

where \(\boldsymbol{\omega}\left(\mathbf{I}_0\right)\) is the frequency vector that characterizes the type of motion displayed by the trajectories of the integrable system. Consequently, we have completely solved the motion in the action-angle coordinate space, and since the change of variable from \((\mathbf{q},\mathbf{p})\) to \((\mathbf{I},\boldsymbol{\theta})\) is canonical (symplectic), it is invertible and we can express the solutions to the original Hamiltonian \(H\) in the form \(\mathbf{q} = \mathbf{q}(\mathbf{I},\boldsymbol{\theta})\) and \(\mathbf{p} = \mathbf{p}(\mathbf{I},\boldsymbol{\theta})\).

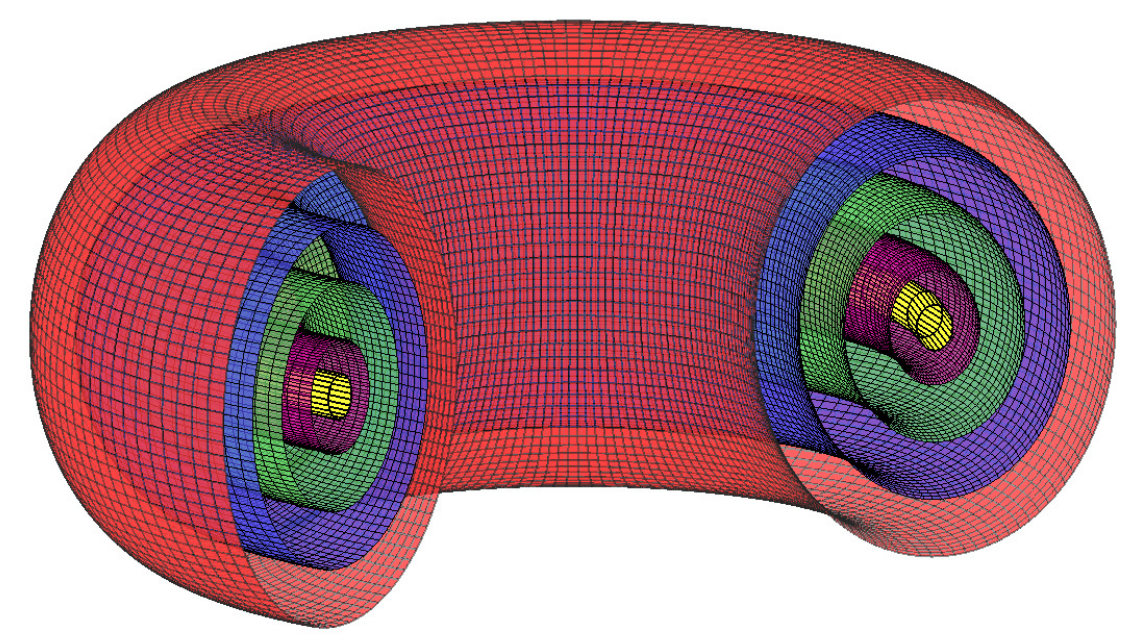

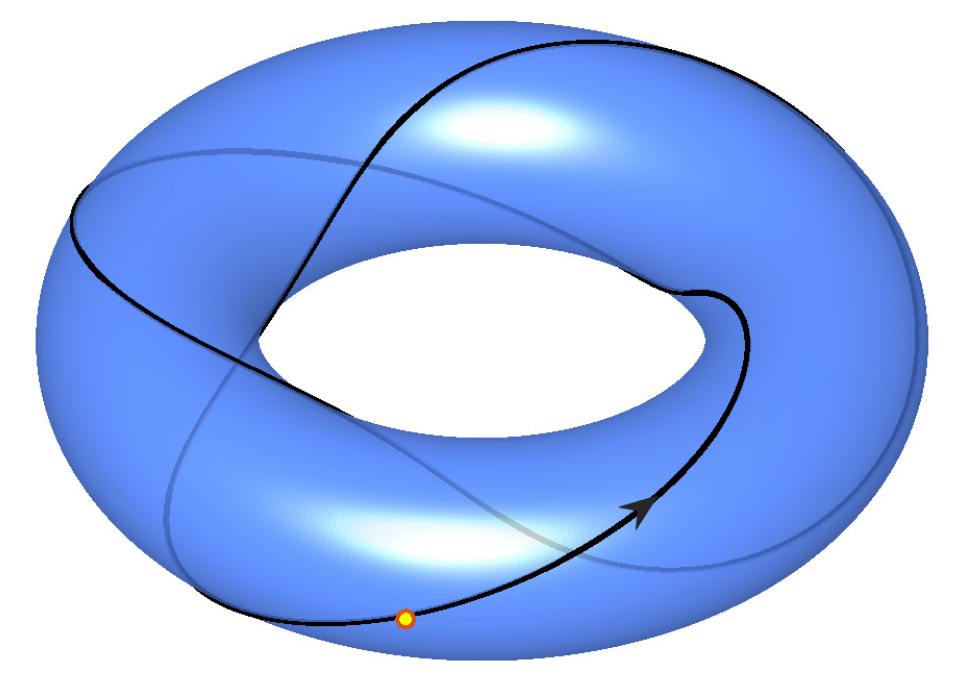

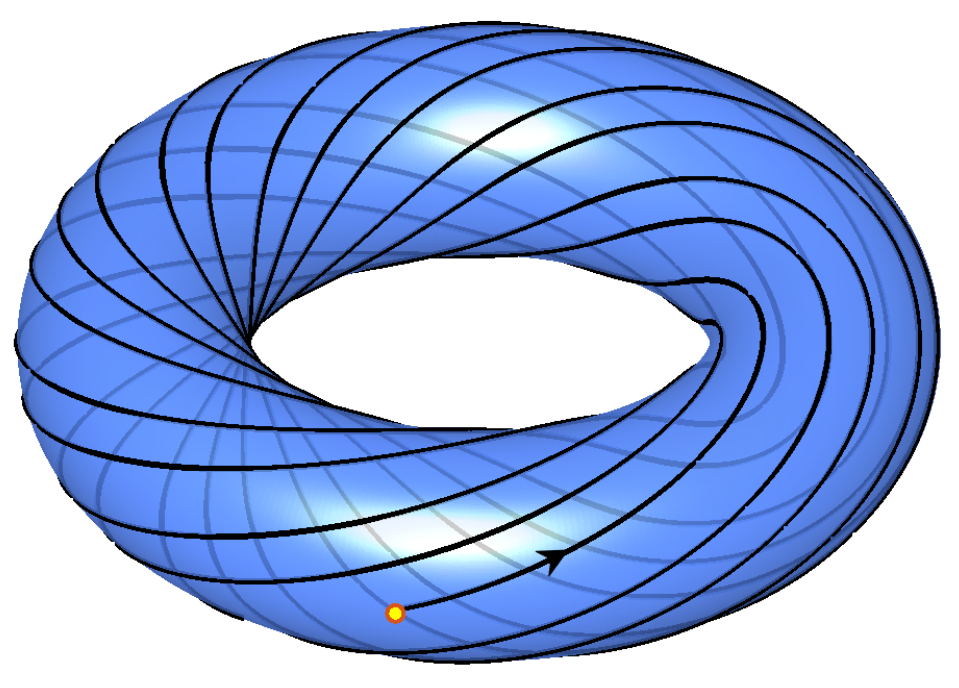

Equations (44) and (45) tell us that the flow generated by an integrable Hamiltonian system is linear and takes place on invariant \(N\)-dimensional tori parametrized by \(N\) angle variables. This behavior is known as quasiperiodic motion. Invariance means that a trajectory starting on one of these tori will never leave that torus. Given an energy level for the Hamiltonian system, this family of tori, which is parametrized by the action variables, foliates the energy manifold. Each member of the tori family can be labelled according to a particular value taken by the actions. In the case of \(N = 2\) DoF, this foliation of the 3D energy hypersurface by 2D tori, similar to many concentric layers of an onion, can be easily visualized. Fig. 15 shows a representation of this geometrical arrangement.

Next we introduce the notion of non-degeneracy of a Hamiltonian, which is a necessary requirement for many results described in the framework of KAM theory.

Kolmogorov non-degeneracy condition: Given an integrable Hamiltonian system in action-angle coordinates \(K = K(\mathbf{I})\), we say that it is non-degenerate if the frequency map:

\[{\mathbf{I} \;\; \mapsto \;\; \boldsymbol{\omega} = \boldsymbol{\omega}(\mathbf{I}) }\]

is a diffeomorphism. In particular, due to the inverse function theorem, a sufficient condition which implies that the Hamiltonian is non-degenerate is the following:

\[{

\det \left(\dfrac{\partial \boldsymbol{\omega}}{\partial \mathbf{I}}\right) = \det \left( \text{Hess}_{K}\right) \neq 0

}\]

At this point, it is important to define what we mean by a resonant and a non-resonant torus, because the informal statement of the main results of KAM theory that we gave at the beginning of this section relies heavily on this concept. Recall that KAM theory studies the conditions under which the tori of an integrable Hamiltonian persist when the system is subjected to a small perturbation.

Resonance: The frequency vector \(\boldsymbol{\omega} \in \mathbb{R}^{N}\) is said to be resonant if there exists a vector of integers with at least one of its components not zero, that is, \(\mathbf{k} \in \mathbb{Z}^{N} - \lbrace 0 \rbrace\), such that:

(46)\[\begin{equation}

\mathbf{k} \cdot \boldsymbol{\omega} = \sum_{i = 1}^{N} k_i \, \omega_i = 0.

\end{equation}\]

Otherwise \(\boldsymbol{\omega}\) is non-resonant. Tori characterized by a resonant (or non-resonant) frequency vector are known in the literature as resonant (or non-resonant) tori.

Consider the nearly-integrable Hamiltonian:

(47)\[\begin{equation}

\mathcal{H}(\mathbf{I},\boldsymbol{\theta}) = h(\mathbf{I}) + \varepsilon f(\mathbf{I},\boldsymbol{\theta})

\end{equation} \]

where \(h\) is the integrable Hamiltonian, \(f\) is the perturbation and \(\varepsilon \geq 0\) is the magnitude of the perturbation. KAM theory establishes that resonant tori are very fragile since they are the first ones to be destroyed when the perturbation is switched on, while most of the non-resonant tori (in the measure-theoretic sense) are robust and survive the perturbation, but become slightly deformed by it. The key ingredient which determines the ``degree of robustness” that allows us to quantify if a torus will survive or not is the frequency vector associated to each of the tori in the integrable system. We give here the basic definitions of these concepts and, for a more detailed analysis, the reader can refer to [Wig03] and references therein.

Add example of 2 DOF harmonic oscillators.

In order to get a better idea and develop some geometrical intuition on the relationship between the definition of resonance and the corresponding dynamical behavior of trajectories on tori, we go back to the simple case provided by an integrable Hamiltonian system with \(N = 2\) DoF. In this context, a resonant torus is determined by a frequency vector \(\boldsymbol{\omega} = (\omega_1,\omega_2)\) that satisfies:

\[{

k_1 \, \omega_1 + k_2 \, \omega_2 = 0 \;,\quad k_1 , k_2 \in \mathbb{Z}-\lbrace 0 \rbrace \quad \Leftrightarrow \quad \dfrac{\omega_2}{\omega_1} = -\dfrac{k_1}{k_2} \in \mathbb{Q}

}\]

Motion on resonant tori is periodic, and hence trajectories are closed. For example, if we consider motion on a torus with frequencies \(\omega_1 = 2\) and \(\omega_2 = 3\), a trajectory lying on this torus will wind around it making \(3\) complete revolutions through the hole on the torus and \(2\) full revolutions around the hole before it closes onto itself. This motion is illustrated in Fig. 17 A).

Interestingly, the resonant and non-resonant tori of the family that fill out the energy manifold of an integrable Hamiltonian system are intermingled in a similar way as the rational and irrational numbers are distributed among the reals. Moreover, it can be shown that almost all tori are non-resonant. This is also the case for rational and irrational numbers, since rationals are dense in the real numbers, but have zero measure. This means that if we select a real number at random, we will almost always pick an irrational number.

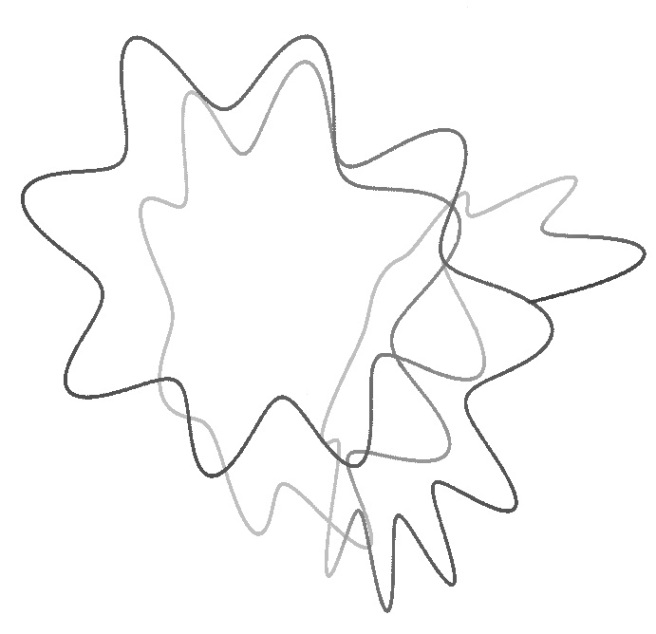

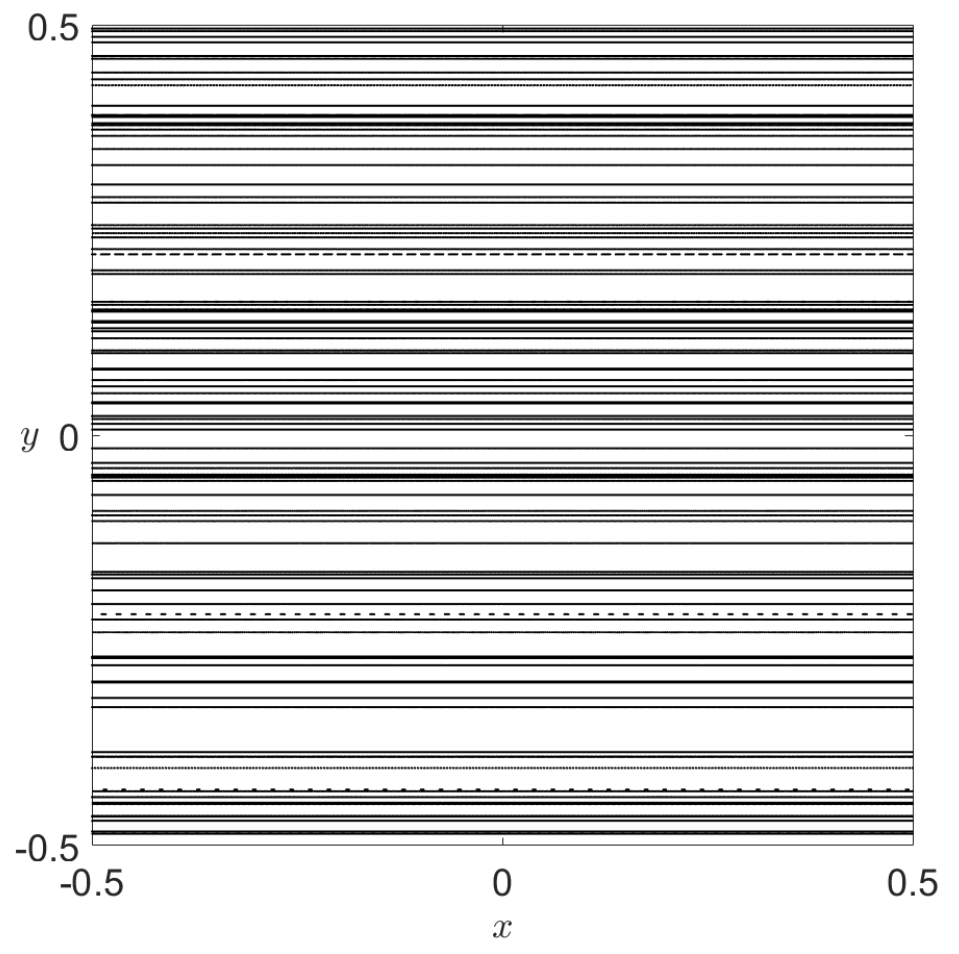

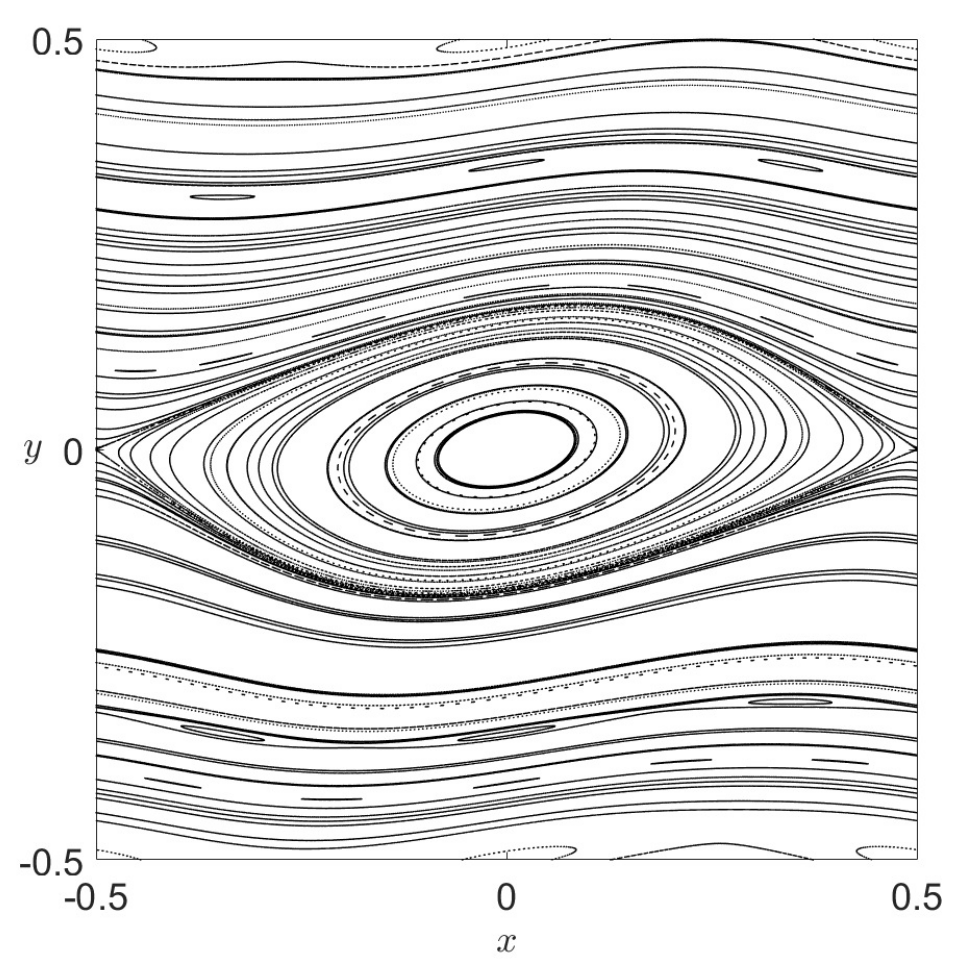

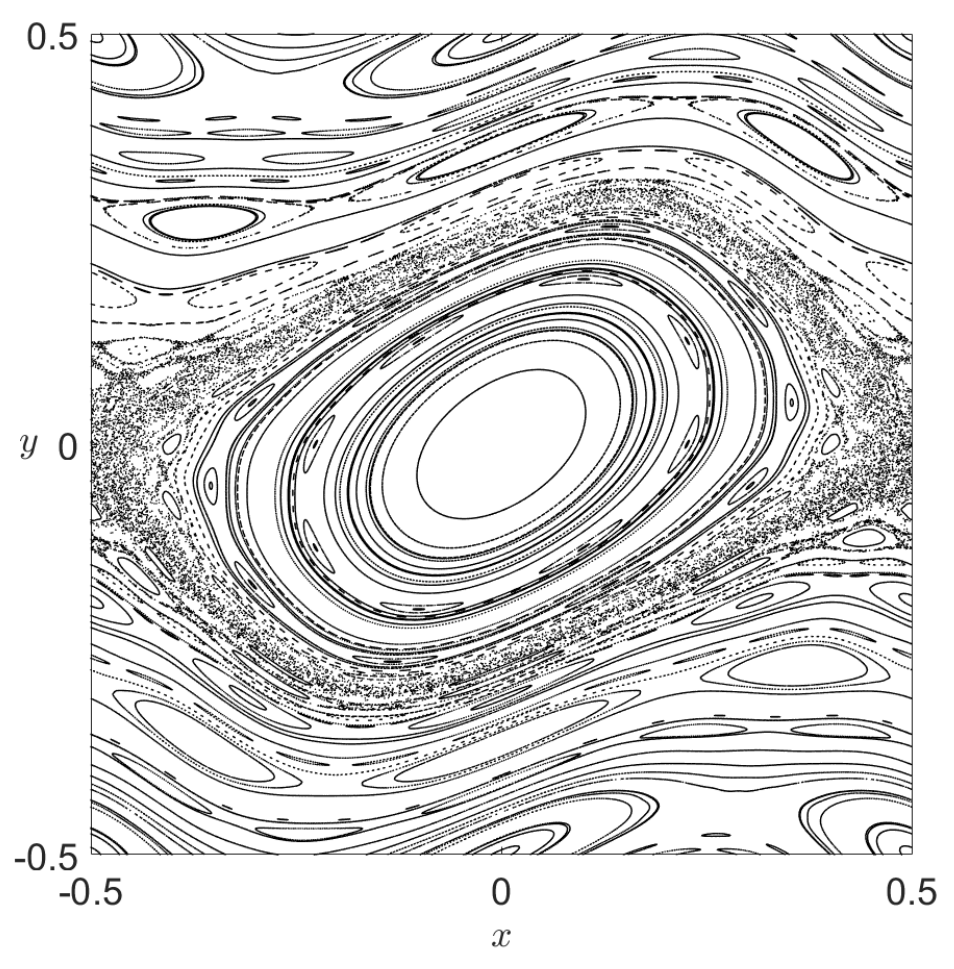

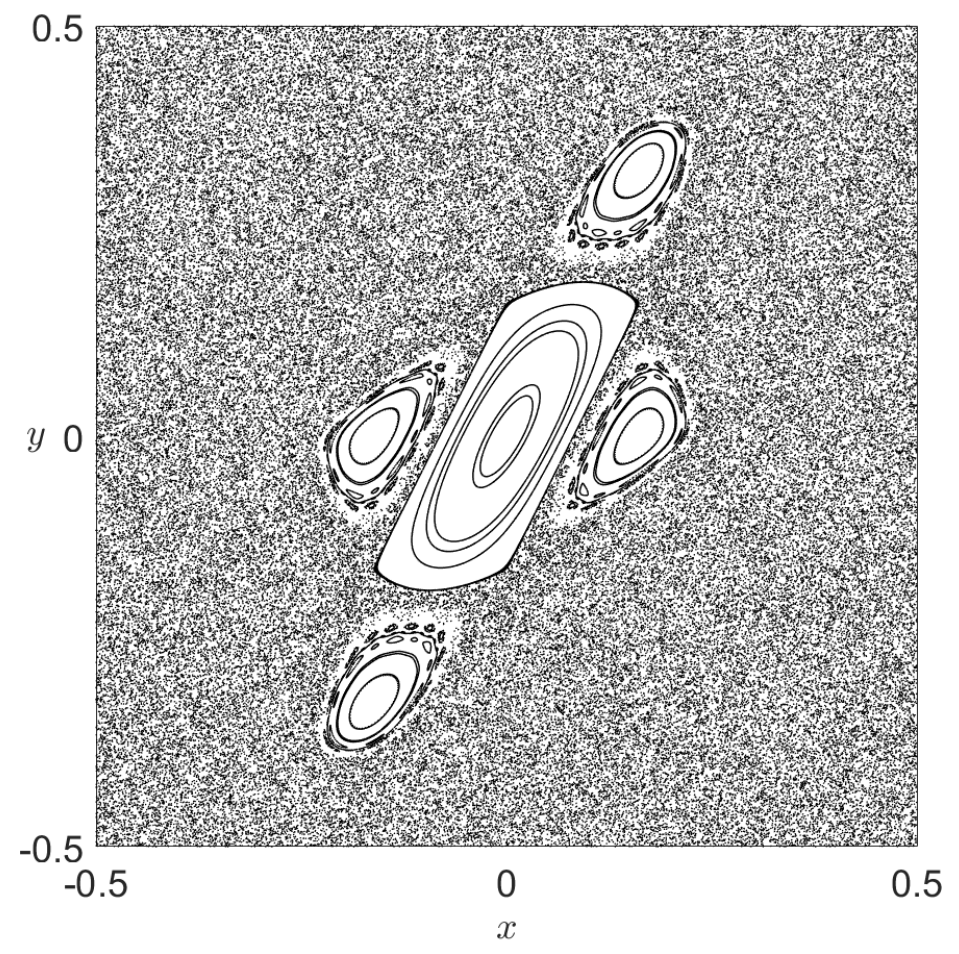

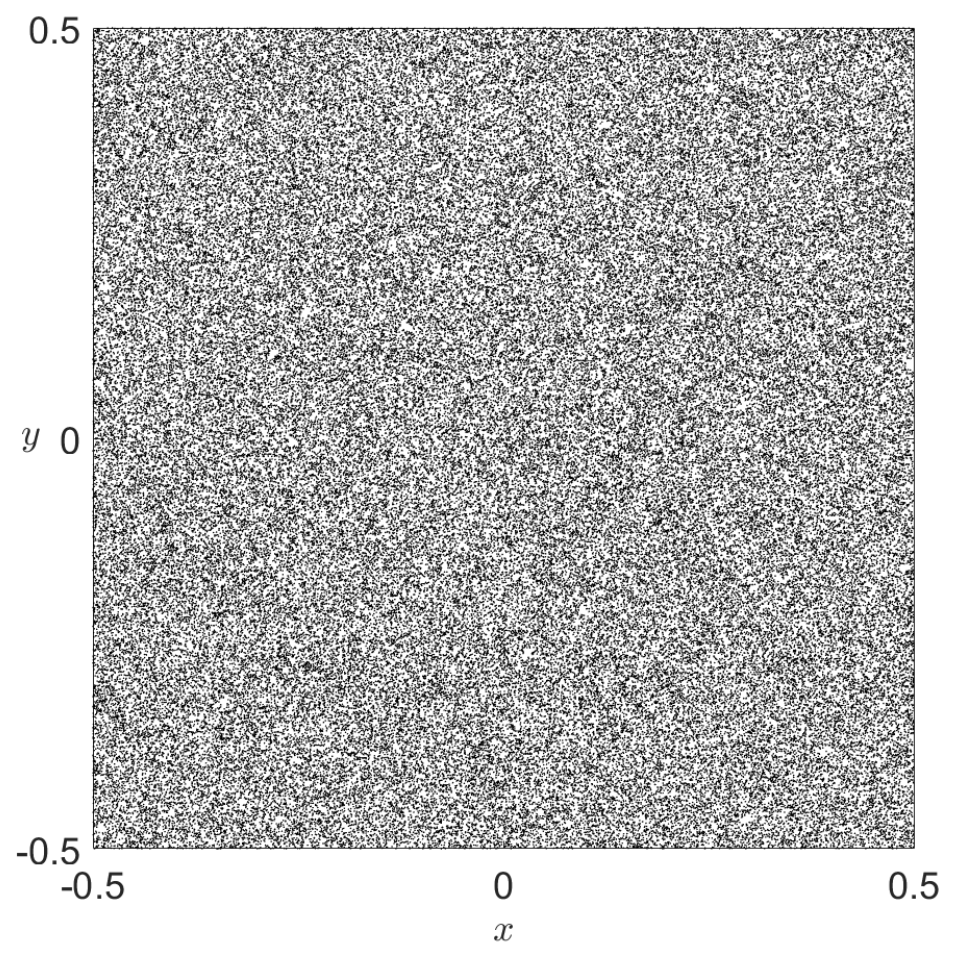

We can illustrate the results discussed by KAM theory by considering tori in the integrable system defined by the Chirikov standard map [Chi79][Mei08] their persistence under perturbation. The Chirikov standard map is a two dimensional symplectic map that displays many features of the Poincaré return maps for typical 2 DoF autonomous Hamiltonian systems. This discrete dynamical system is defined by a two-dimensional area-preserving map which depends on a parameter \(k\) that determines the strength of the perturbation that is applied to the underlying integrable system. The solutions for the unperturbed system (\(k = 0\)) are one-dimensional tori, that is, circles, and are represented in Fig. 23 A). Notice that these tori appear as lines because the left and right boundaries of the domain are identified, and so also, the top and bottom edges of the square. This is the manifestation of the toroidal geometry of the phase space of the standard map. If we increase the perturbation strength to \(k = 0.3\) we observe in panel B) that most of the tori have survived the perturbation, but in a slightly distorted shape. Moreover, we notice also that some of the tori of the originally unperturbed system break (the resonant ones), and in the process they have generated smaller tori, and also hyperbolic points that possess stable and unstable manifolds. Increasing the perturbation further to \(k = 0.8\), one can see in panel C) that non-resonant tori continue to break up into smaller tori, giving rise to structures known as islands of regularity, and that these subregions of the phase space are surrounded by a larger sea of random points that indicates chaotic motion.

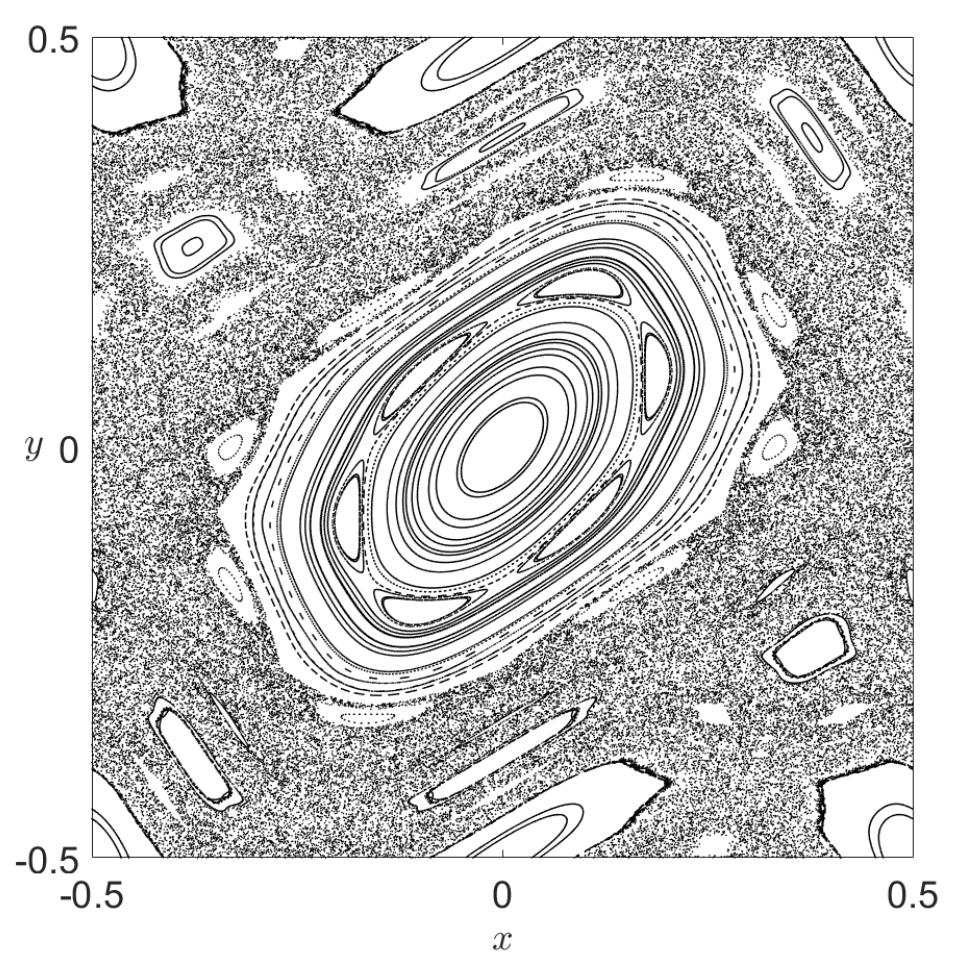

Panels D), E) and F) of Fig. 23 show how with increasing \(k\) all tori eventually break up.

This is in part one of the main messages that can be drawn from KAM theory; the coexistence of chaotic and regular motion in the phase space of Hamiltonian systems [MM74]